A price floor or a minimum price is a regulatory tool used by the government. More specifically, it is defined as an intervention to raise market prices if the government feels the price is too low. In this case, since the new price is higher, the producers benefit. For a price floor to be effective, the minimum price has to be higher than the equilibrium price.

For example, many governments intervene by establishing price floors to ensure that farmers make enough money by guaranteeing a minimum price that their goods can be sold for. The most common example of a price floor is the minimum wage. This is the minimum price that employers can pay workers for their labor.

The opposite of a price floor is a price ceiling.

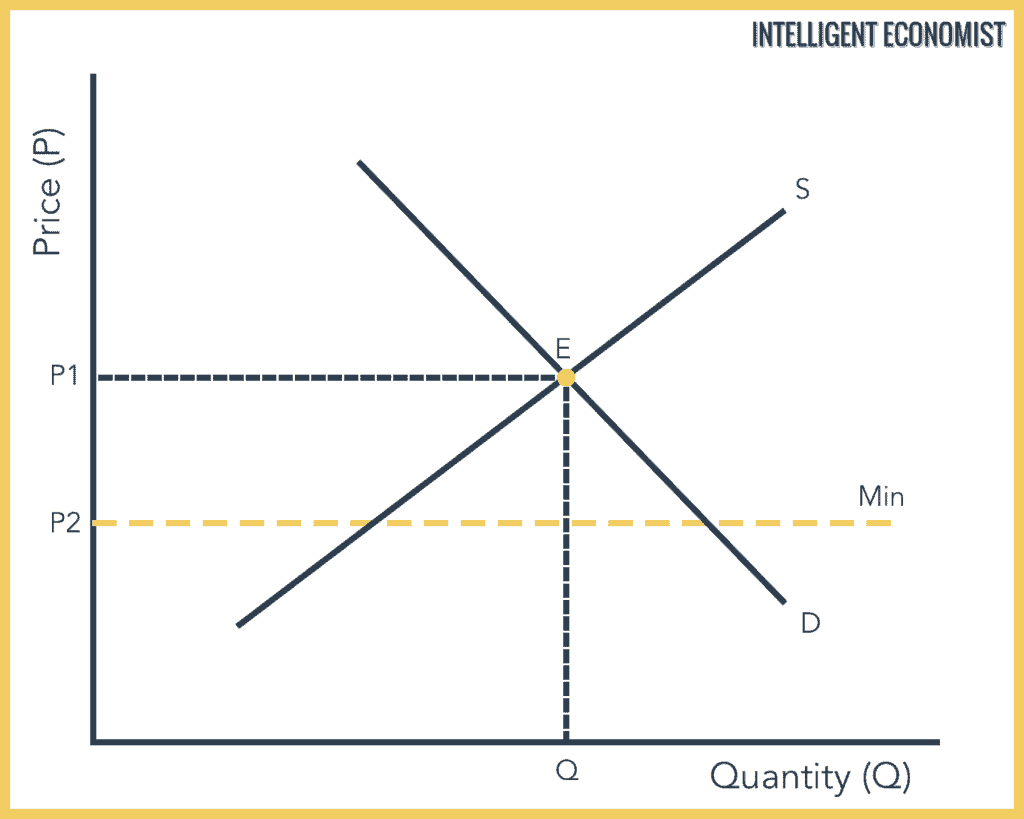

A Price Floor Graph

For a price floor to be effective, it must be set above the equilibrium price. If it’s not above equilibrium, then the market won’t sell below equilibrium and the price floor will be irrelevant. In the diagram above, the minimum price (P2) is below the equilibrium price at P1. Since the equilibrium price is higher, this price floor will be ignored.

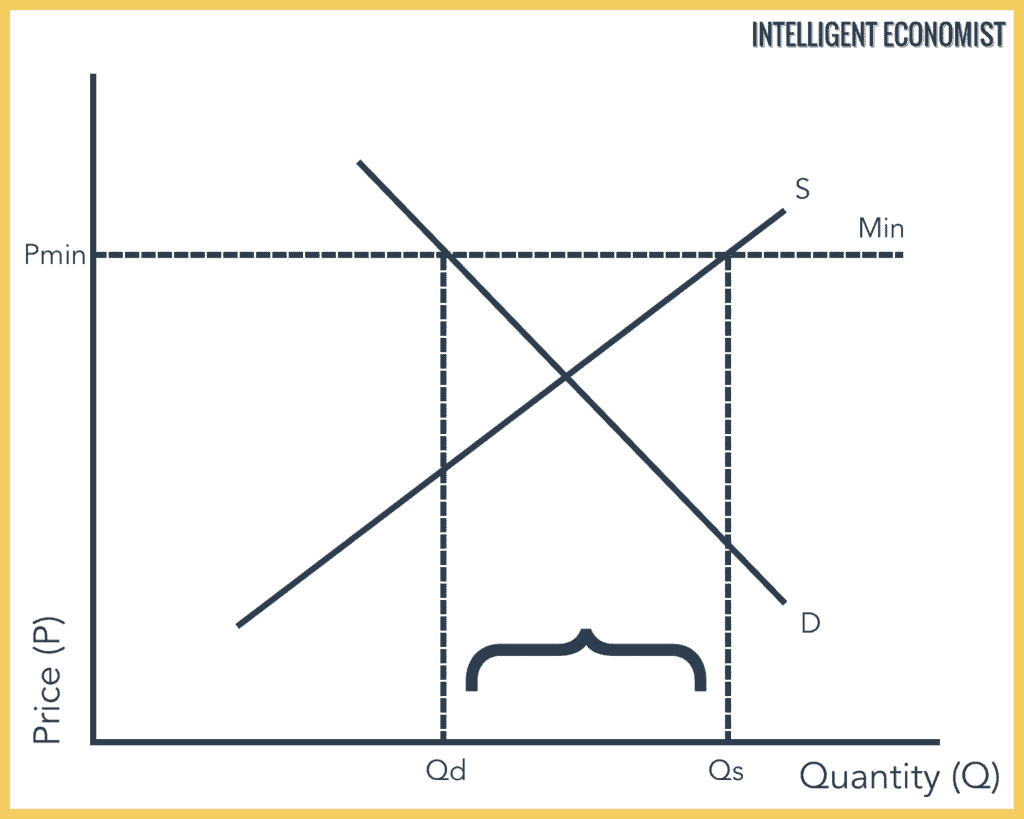

In the price floor graph below, the government establishes the price floor at Price Pmin, which is above the market equilibrium. The result is that the Quantity Supplied (Qs) far exceeds the Quantity Demanded (Qd), which leads to a surplus of the product in the market.

Binding Price Floor

A binding price floor is a required price that is set above the equilibrium price. The government is inflating the price of the good for which they’ve set a binding price floor, which will cause at least some consumers to avoid paying that price. This has the effect of binding that good’s market. The result is a surplus of the good, due to unsold goods. Governments can institute binding price floors by setting laws that do not allow goods to be sold at market rates. They can also do so by artificially manipulating demand—buying extra goods causes the price of those goods to increase, such that it is above the rate of the binding price floor.

For instance, if the minimum wage in a particular state is $12, and a company would like to pay their employees $14 per hour, this is not an issue—this is not a binding price floor. Conversely, if a company would like to pay employees $10, this will not work, because that amount is lower than the price floor—in this case, it is a binding price floor.

In other words, if you start at a price of, say, $50, and then keep lowering the price, which price do you hit first? If you arrive at the price floor price first, that means it is binding. And if you arrive at the equilibrium price first, this means the price floor is not binding.

Real-World Price Floor Example

Minimum Wages

Minimum wage laws set legal minimums for the hourly wages paid to certain groups of workers. In the United States, amendments to the Fair Labor Standards Act have increased the federal minimum wage from $0.25 per hour in 1938 to $5.15 in 1997. Minimum wage laws were originally created in Australia and New Zealand in order to guarantee a minimum standard of living for unskilled workers. Some people believe that minimum wage laws protect workers from exploitation by employers and reduce poverty. Many economists believe that minimum wage laws can cause unnecessary hardship for the very people they are supposed to help.

The reason is that although minimum wage laws can set wages, they cannot guarantee jobs. In practice, minimum wage laws can price low-skilled workers out of the labor market. Employers typically are not willing to pay a worker more than the value of the additional product that he produces. This reality means that an unskilled youth who produces $4.00 worth of goods in an hour will have a tough time finding a job if he must, by law, be paid $5.15 an hour.

Effects of a Price Floor

In the end, even with good intentions, a price floor can hurt society more than it helps. It may help farmers or the few workers that get to work for minimum wage, but it does not always help everyone else. If the market was efficient prior to the introduction of a price floor, price floors can cause a deadweight welfare loss. A deadweight loss is a loss in economic efficiency.

Consumers must now pay a higher price for the exact same good. Therefore, they reduce their demand or drop out of the market entirely. Meanwhile, suppliers find they are guaranteed a new, higher price than they were charging before. As a result, they increase their production. The problem is that this creates excessive supply, in which case the government ends up buying and stockpiling the extra quantity. Often the government destroys the surplus or allows it to spoil.

The government also has the option to subsidize consumption to encourage more demand. If the government sells the surplus in the market, then the price will drop below the equilibrium. A price floor also leads to market failure (a situation in which markets fail to efficiently allocate scarce resources).

appropriate follow up to your price ceiling article, quells the curiosity as to if there is an opposite to price ceiling.

nicely written.. the brevity is much appreciated.

i love your blog so far! keep writing!