Perfect competition or pure competition (sometimes abbreviated to PC) is a type of market structure. It is important to note that this form of market structure does not actually exist in the real world and is thus considered to be theoretical. As an economic theory, then, it does not seek to literally describe reality but to stand as an “ideal type” against which markets in the real world can be compared and contrasted. In a perfectly competitive market:

- There are very many small firms

- All of these firms sell the same homogeneous product, often classified as a commodity

- There are no barriers to entering or exiting the market

- Both producers and consumers have perfect knowledge (for the present, as well as the past and future) regarding the nature and price of the product for sale from each firm

- All firms in the market are price takers, meaning they do not have the power to affect the price of the goods they sell

- Transportation for goods is affordable and efficient

- There are no government controls on the market

Where there is perfect competition, prices are a direct representation of the forces of supply and demand. Profits are limited for firms—they are only able to make enough to keep their business going, rather than any additional profits. This is because profits at any level higher than that would draw new firms into the market and automatically bring profits back down to a normal level.

Perfect vs. Imperfect Competition

Compare perfect competition with imperfect competition, which is a market (real or hypothetical) that does not show all of the features of perfect competition as described in the next section. Theories surrounding comparison of perfect and imperfect competition come out of post-classical economic thought in the well-known, influential Cambridge tradition.

Characteristics of Perfect Competition

1. Number of Firms

There are very many small firms, too many to count. An apt comparison would be to the grains of sand on a beach. Because all of the participating firms are so small, they are not able to alter prices via changes in supply (see number five on this list, “Price Takers”). With so many sellers as well as buyers in such a market, supply and demand do not fluctuate significantly but stay relatively steady.

A perfectly competitive market is the direct opposite of a monopolistic market. In a monopoly, just one firm produces a particular good. This allows that firm to charge as much as it wants, because consumers cannot buy the good elsewhere and competitors aren’t able to join the market and sell the good at a more affordable price point.

2. Homogeneous

All producers of a good sell the same product(s), which means that the products are homogeneous or identical. The products themselves cannot be differentiated with features like distinctive branding or even color, size, or shape. Such a product may be classified as a commodity. The result is ease of substitution, as well—a buyer can choose to buy the good from one firm or another without experiencing any difference in the product they receive.

3. Barriers to Entry

There are no barriers to enter or exit the market. (In other cases, sometimes high costs or strict regulations prevent firms from entering.) This means that sunk costs are low. Sunk costs are those that, once paid, can never be recouped, e.g. advertising at the start of participating in an industry.

4. Perfect Information

All consumers and producers have “perfect information,” which means that everyone knows the price of the product from each firm, and the overall supply and demand for that good. This perfect information access extends not just to the present but also the past and future. This has the effect of allowing all firms to produce goods like those of other firms, using the same methods and without any reduction in efficiency from producer to producer.

Contrast a market with perfect information accessibility with industries in which proprietary knowledge and research are enormously important to generating profits and maintaining a stronghold over the market. One of the most significant examples would be the pharmaceutical industry, in which knowledge of patents and research being conducted by competing firms allow firms to be much more competitive.

5. Price Takers

No single firm can influence the market price, or market conditions. Firms sell all they produce, but they cannot set a price. They are said to be “price takers.” For a firm to be a price taker, its demand curve must be perfectly elastic.

6. Affordable, Streamlined Transportation Options

Markets with perfect competition do not require that firms expend significant financial output for transportation, thanks to efficient and affordable transportation infrastructure or lack of a need for significant transport. As a result, goods are cheaper and they arrive where they need to go quickly and without interruption.

7. No Controls

In many cases, government regulation, price controls, and so forth have an enormous amount of influence over markets. This influence extends to market formation for products. It also extends to firms’ entry and/or exit into markets based on rules set by the government for a given market. To use the example of the pharmaceutical industry once again: the FDA sets many requirements regarding drug research, production, and sales.

While often necessary, as in the case of the pharmaceutical industry, requirements set by the government make it more costly to enter an industry. This means that firms must expend significant amounts on capital investments like employees and infrastructure. For the drug industry specifically, firms spend quite a bit on lawyers as well as machines to manufacture their pharmaceutical products, for example. The cost of just one drug entering the market is thus much higher.

Compare this to the tech industry, where many start-ups can build a business with very little capital at all because of few government regulations and controls. In a perfectly competitive market, entry and exit are not costly (as stated in point number three on this list), and this is in part because of a lack of regulation of said entry/exit.

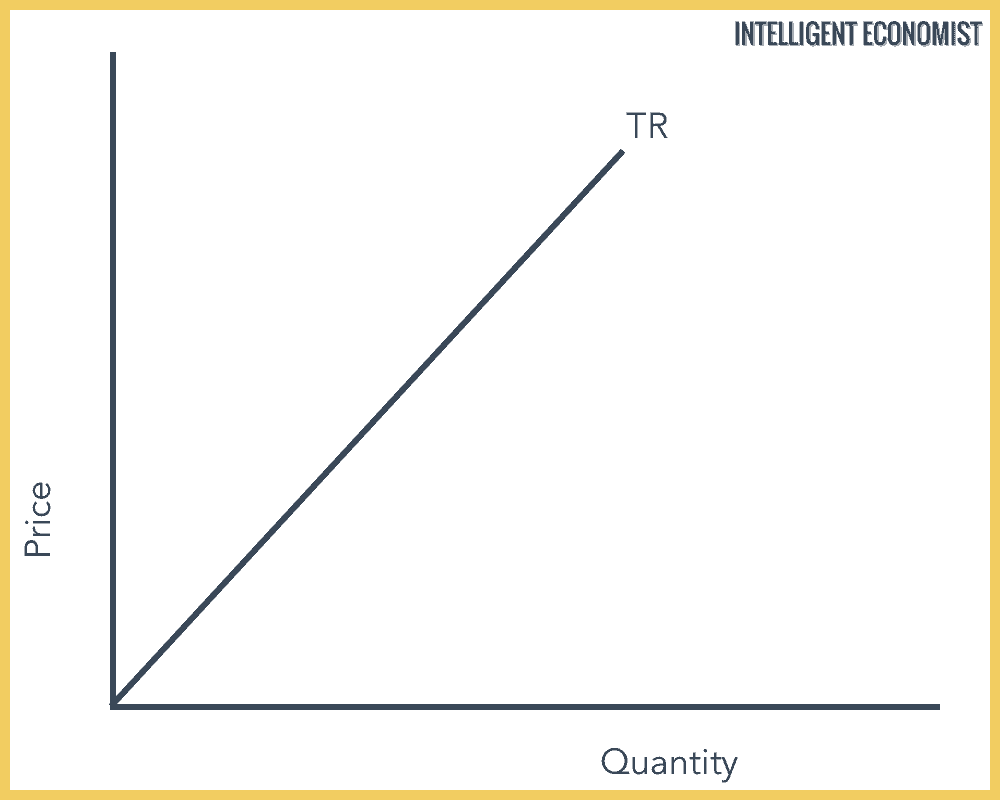

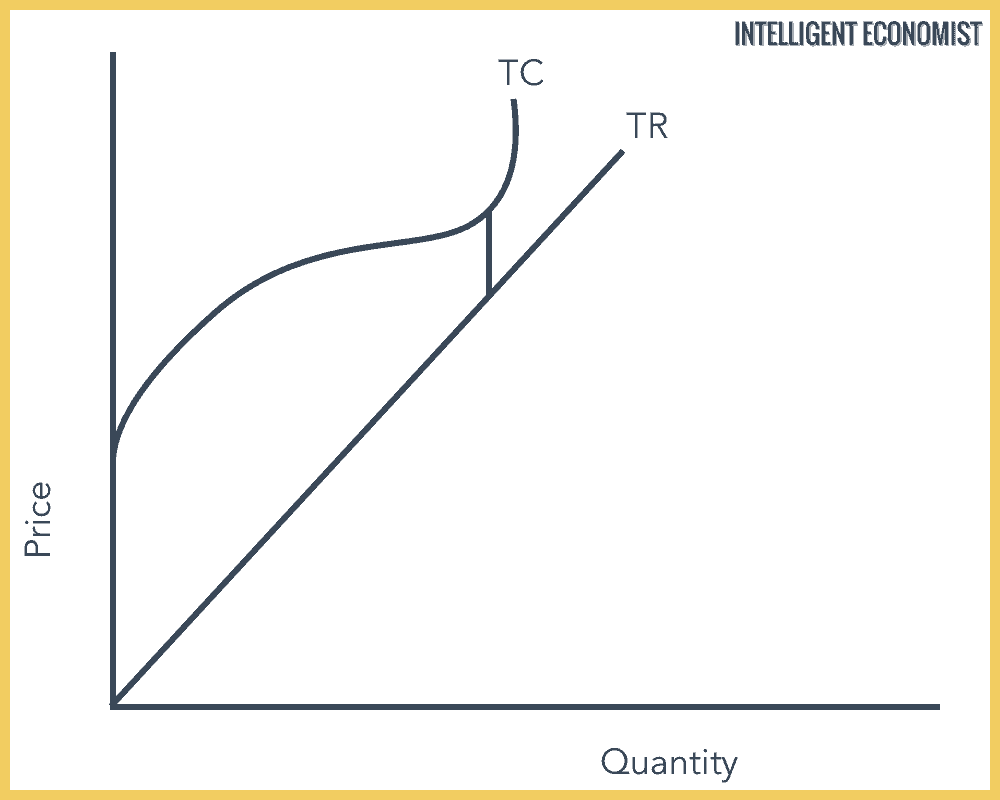

Perfect Competition Total Revenue Curve

Total Revenue is Total Quantity x Price. Since producers can sell all they produce, and the price is fixed, revenue will increase with each good sold at a constant rate. That explains the shape of the Total Revenue curve (TR).

Perfect Competition Examples

Perfect competition does not exist in the absolute form in the real world, as it is primarily a theoretical market structure. However, there are some real-world examples that come close to perfect competition—these are generally very competitive, liquid markets for comparable commodities. Here are several industries that exemplify elements of perfect competition, without actually achieving true perfect competition:

1. Internet Sellers

With the advent of internet sales, many markets have come much nearer to perfect competition. This is because compared to real-life sales, the internet makes price comparison between sellers significantly easier. This fulfills the important perfect competition criterion of perfect information. Also significant is the fact that with the internet, barriers to entry for firms are significantly lower.

For instance, almost anyone can sell products on eBay. Buyers can compare identical goods for sale by numerous sellers on eBay and find the least expensive version of that good. This has an effect on profits as well. Internet book-selling, for instance, has made many books significantly less expensive, with the result that many book-sellers make just normal profits from their sales.

2. Foreign Exchange Markets

First, currency is homogeneous—one significant factor in perfect competition. Additionally, those who are trading currency have a broad array of buyers and sellers accessible to them. Price comparison between sellers is also notably very easy, with plenty of information about trading options highly accessible, making this an industry that is much closer to “perfect information” than many others.

3. Agricultural Markets

One significant criterion of perfect competition is homogeneity, meaning that the products being sold are identical. When farmers sell their goods on the agricultural market, many are selling identical products (the same variety of wheat, for instance). Within these agricultural markets, buyers can also engage in price comparison without much difficulty at all. This allows agricultural markets to approach a state of perfect competition to a much greater degree than many other industries.

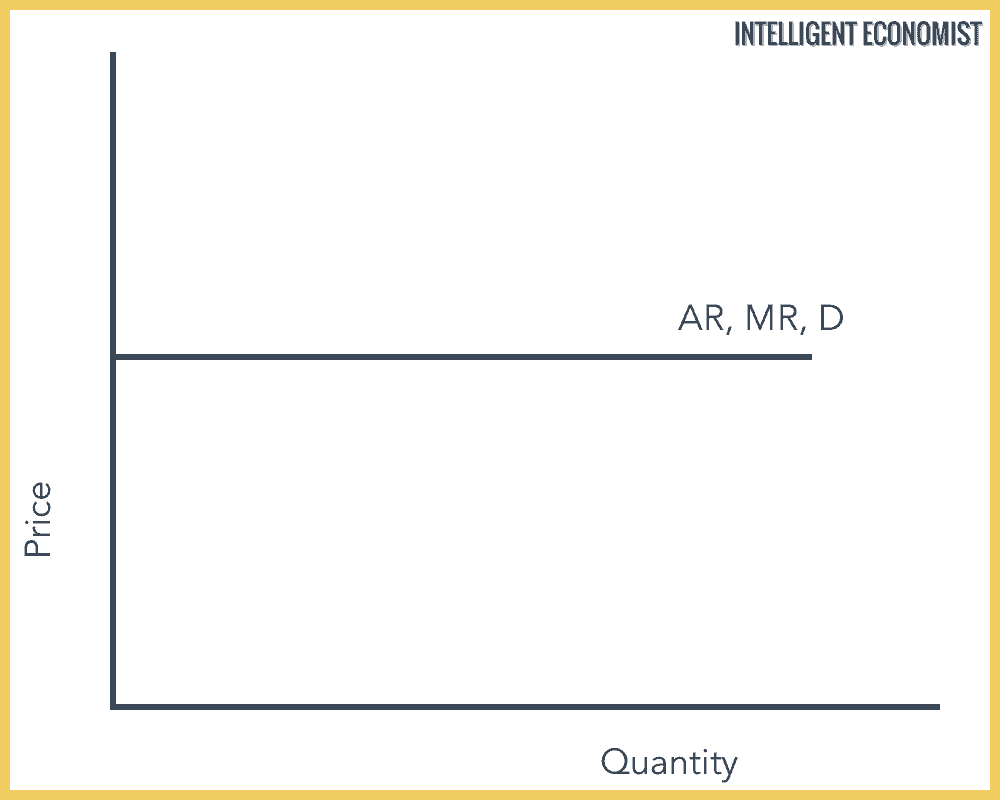

Marginal & Average Revenue Curve

A. Marginal Revenue

The revenue earned by selling one more unit. In perfect competition, every unit is sold at the same price, so revenue earned from each new unit would be the same as before. That explains why the Marginal Revenue curve (MR) is completely horizontal.

B. Average Revenue

Average Revenue is Total revenue/Quantity. Since all the units are the same price, each new unit would have the same average revenue, so the Marginal Revenue = Total Revenue.

Price (P) = AR = MR (in Perfect Competition)

Perfect Competition in the Short Run

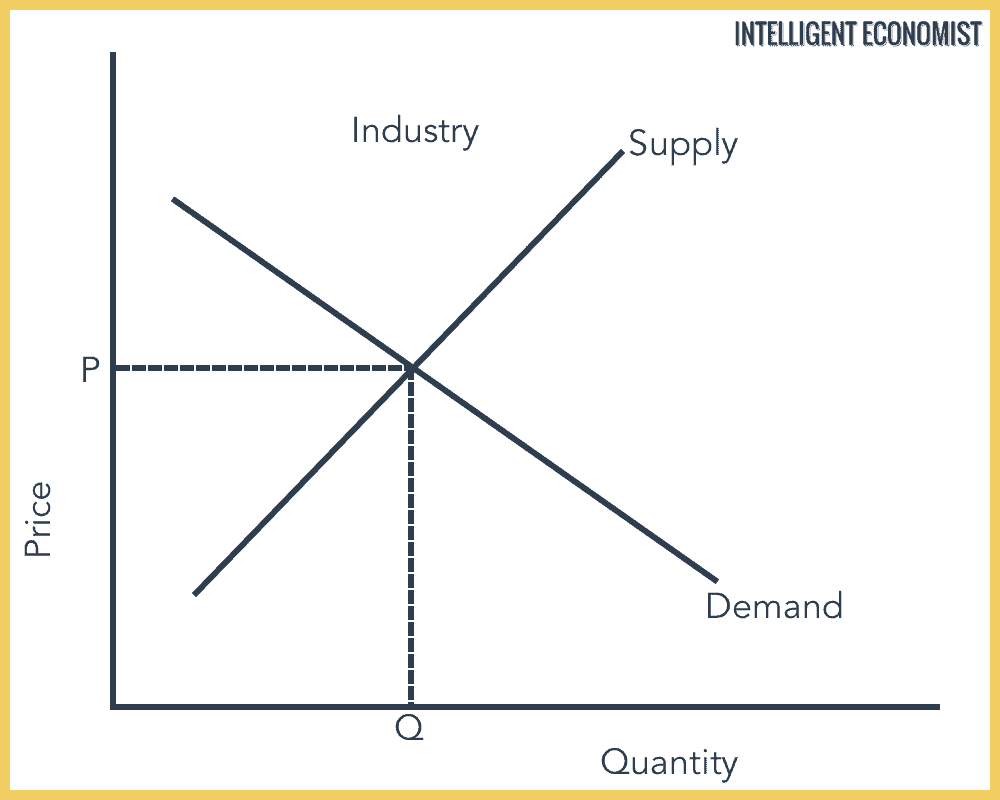

Perfect Competition Short Run Industrial Equilibrium

Firm as a Price Taker

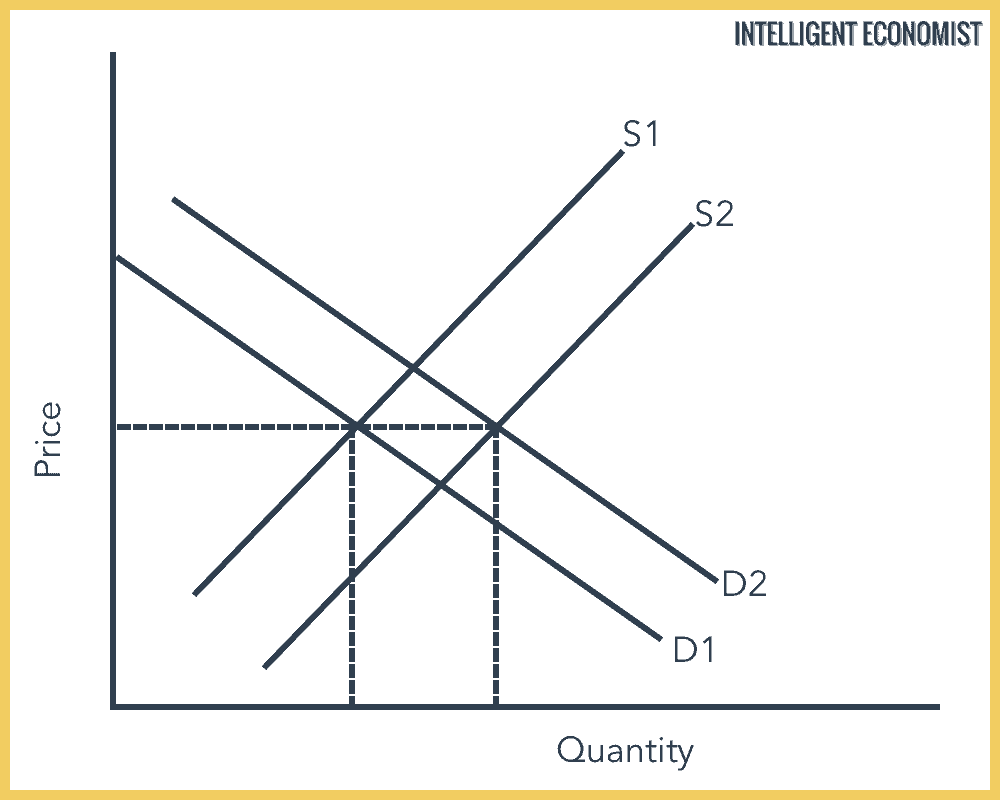

To understand what ‘Price Taker’ means, look at the diagram below. The first diagram is the industry supply & demand, while the one below it is the individual firm. If a firm tries to lower or increase the price, then either everyone will buy from them or no one will buy from them, but they have no incentive to sell lower than the industry since they are already selling everything they produce.

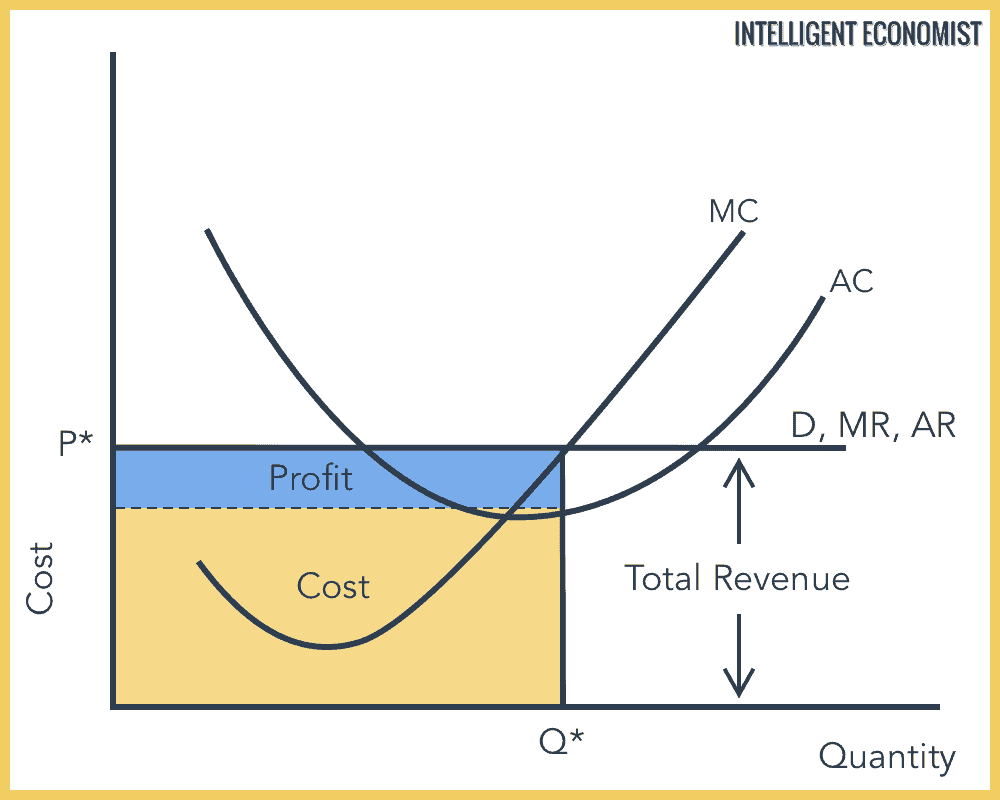

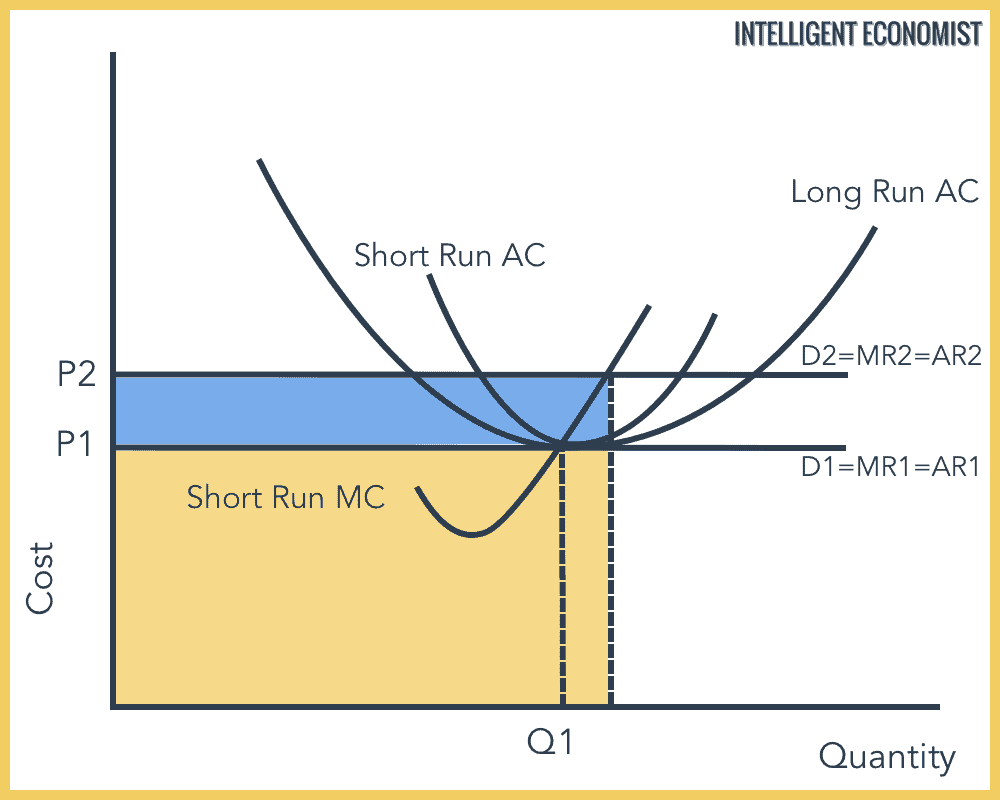

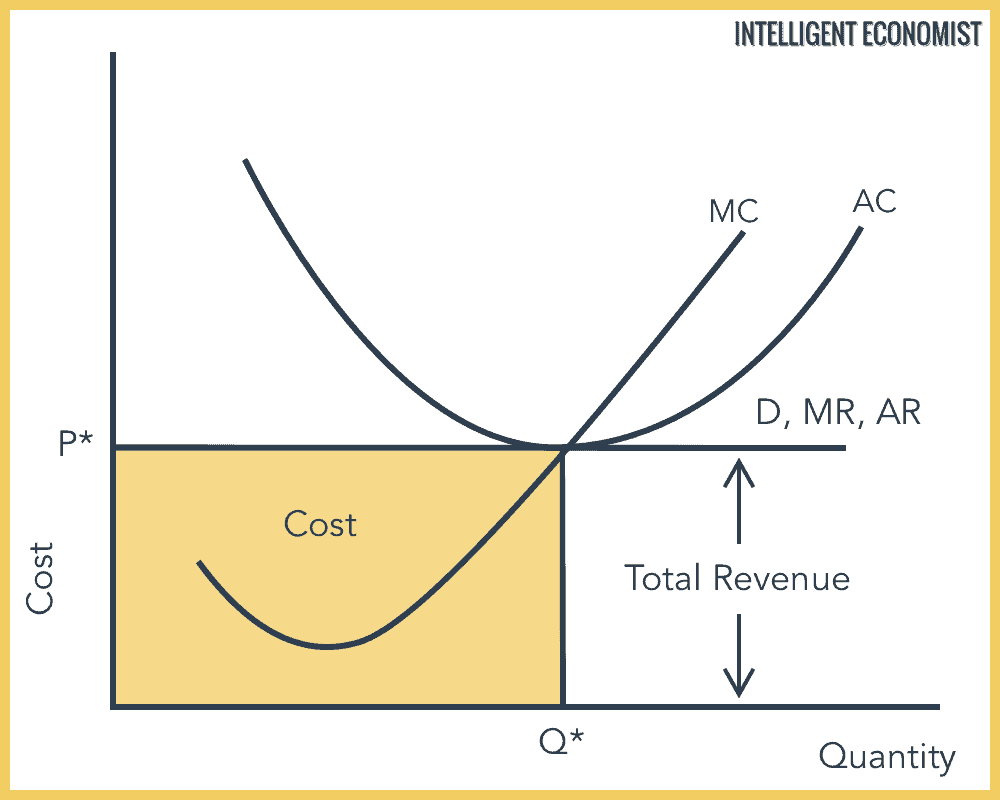

Perfect Competition Short-Run Equilibrium: Supernormal Profits

In the diagram above, the firm is making supernormal profits. The total cost to the firm is in blue, and the profit is in the red. We can intuitively tell it makes a profit because its average costs are lower than the average revenue. To calculate the cost, see where the quantity hits the average cost line, and then draw a horizontal line to the Y-axis. Whatever area is above the cost is the profit or the loss.

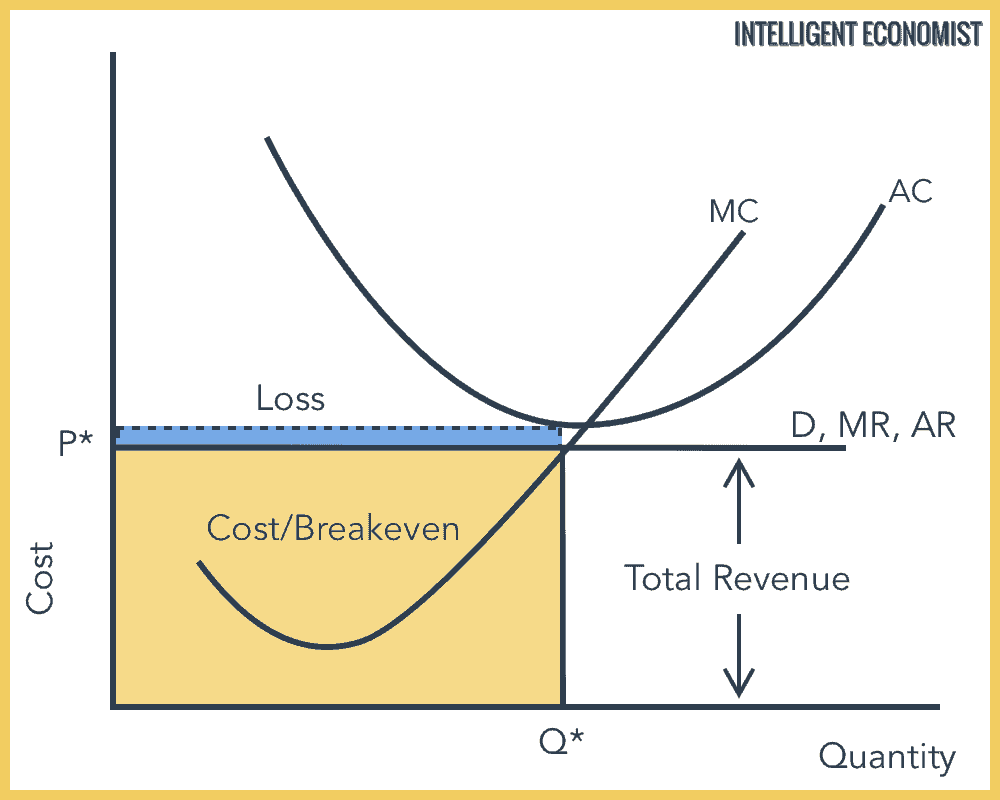

Since we assume that all individual firms are profit maximizers, we take MC = MR for profit maximization. If a company is loss-making, the rule still applies, so the loss is minimized. Similarly, the least Total Cost is taken to maximize profit or minimize loss.

Perfect Competition Short Run Losses

Perfect Competition Short Run Equilibrium Loss Making

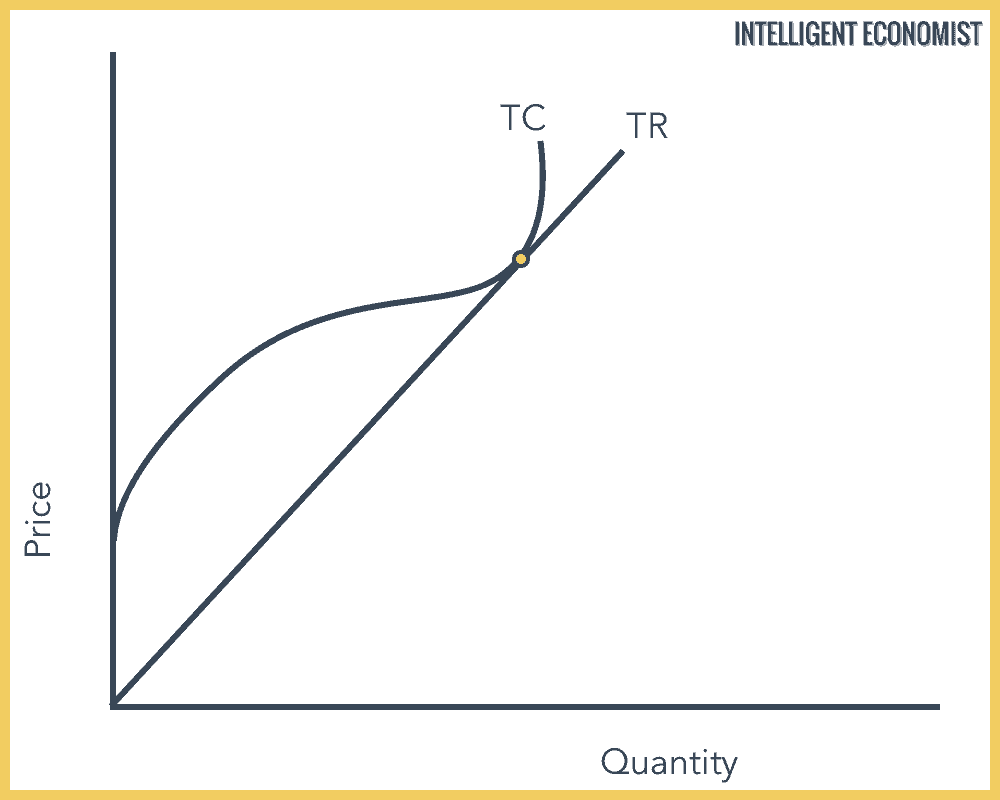

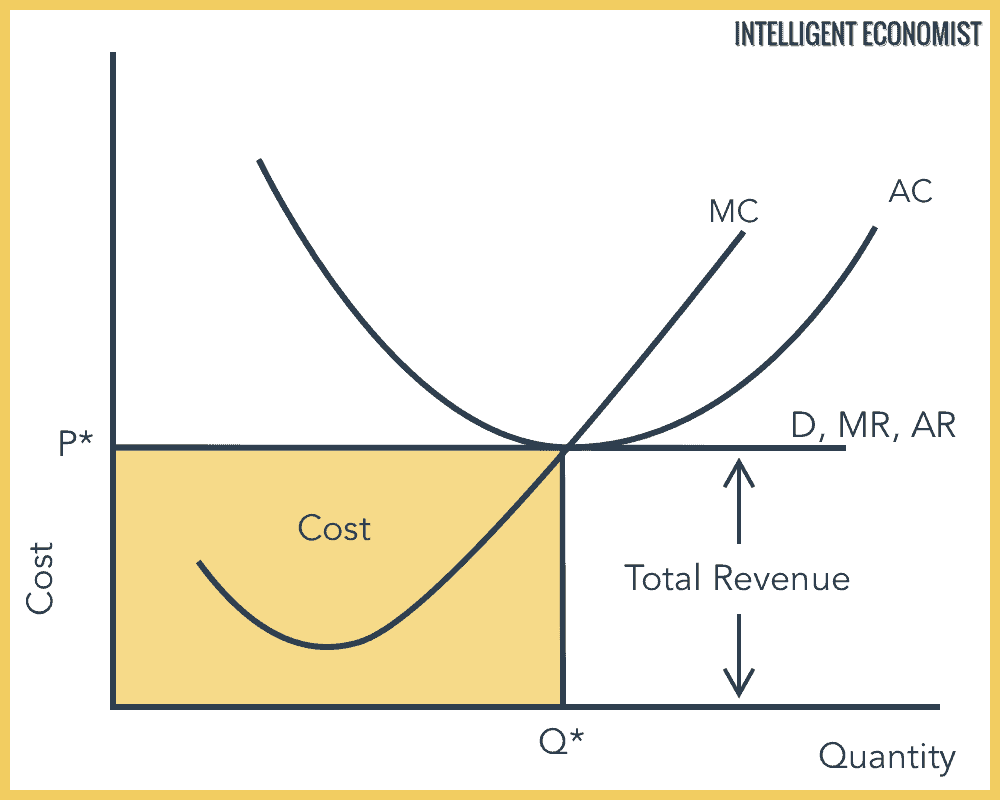

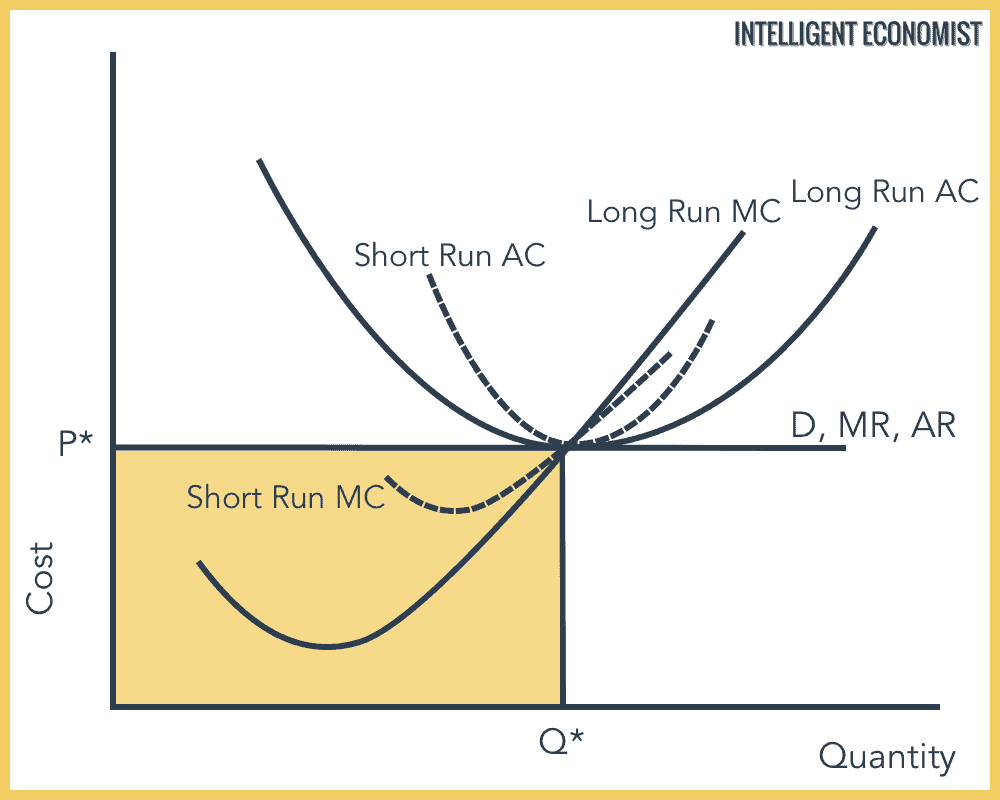

Normal Profit/Break-even

Perfect Competition Short Run Zero Economic Profits

Leaving the Industry

In the Perfect Competition short-run, the firm will continue to produce if he can recover the average variable cost, as fixed costs are paid regardless of production.

Perfect Competition in the Long Run

In the long run, we assume that all Factors of Production are variable, which means that the entrepreneur can adjust plant size or increase their output to achieve maximum profit. Perfect Competition Long Run equilibrium results in all firms receiving normal profits or zero economic profits.

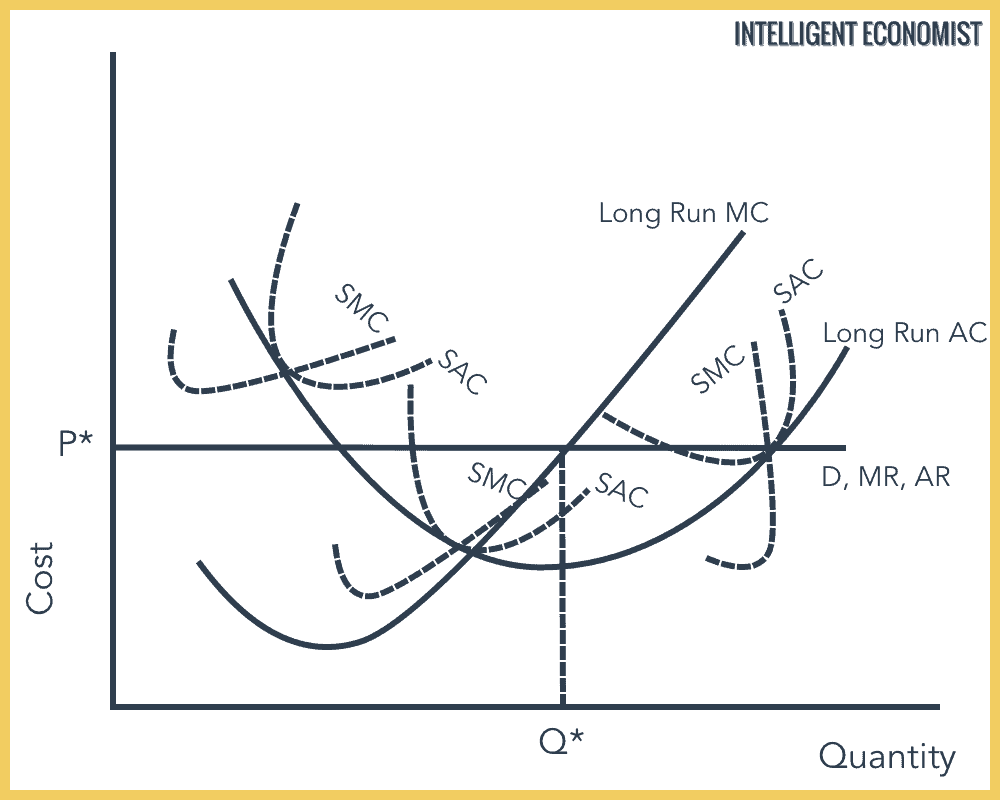

Perfect Competition Long Run Factor Mobility

The Short Run Average Cost (SAC) curves that are above the Average Revenue curve (AR), i.e. the two curves to the extreme left and the extreme right are loss-makers that will either leave the industry or change plant size in the long run. The three lower Short Run Average Cost (SAC) curves are making supernormal profits. Supernormal profits occur when total revenues exceed the total cost (including the compensation of risk undertaken by the entrepreneur). These supernormal profits will attract outer firms into the industry.

Perfect Competition Long Run Equilibrium

In the long run, with the entry of new firms in the industry, the price of the product will go down as a result of the increase in supply of output and also the cost will go up as a result of more intensive competition for factors of production. The firms will continue entering the industry until the price is equal to average cost so that all firms are earning only normal profits.

The short-run cost curves that lie at the lowest point of the long run average cost curve has no incentive to leave the industry.

The firms will continue leaving the industry until the price is equal to average cost so that the companies remaining in the field are making only normal profits. Normal Profits, also known as the break-even or zero economic profit, includes the profit paid to the entrepreneur (included in the total cost, for bringing in scarce resources and taking on risk), and the total cost is equal to total revenue. A firm making normal profits will remain in the industry.

In the Perfect Competition Long Run, the loss-making firms will exit the industry, and new firms will enter the market. Losses are the key to establishing Long Run equilibrium.

In the long run equilibrium, firms enjoy market efficiencies, which leads to scarce resources not being wasted.

Perfect Competition Long-Run Profit Maximization Formula

Where Long Run Marginal Cost (Long Run MC) = Short Run Marginal Cost (SMC) = Marginal Revenue (MR)

1. Productive Efficiency

When the firm produces at the lowest short-run average cost, they can achieve productive efficiency, where price equals the minimum average total costs. Therefore, any firm that cannot produce at the minimum Average Total Cost will be forced to leave the industry.

2. Technical Efficiency

Technical Efficiency is when the firm produces the maximum average product. This efficiency is also a consequence of productive efficiency.

3. Allocative Efficiency

Allocative Efficiency is when the price is equal to marginal cost. The firm achieves the greatest allocative efficiency when there is no other combination of goods and services that would be more desired by society.

Disadvantages of Perfect Competition

1. Lack of Innovation

Firms do not have an incentive to innovate or spend on research and development because other firms can easily copy their products. This disincentive is a distinctive characteristic of the perfectly competitive market.

Firms are further disincentivized to innovate by the fact that no firm can gain a dominant market share in a perfectly competitive market. Gaining a dominant market share would motivate firms to try to distinguish themselves from their competitors by producing better-quality products.

2. Less Variety of Products

This one is fairly straightforward, but it is significant for its effect on overall happiness and free choice of consumers. Since firms all produce the same product, there is less variety available to consumers.

3. Fixed Profit Margins

As described early on in this article, profit margins are directly linked to supply and demand. Firms cannot charge more for their goods based on higher quality and gain higher profits. Lack of profit margins prevents firms from capital investment to increase their total production ability and levels.

4. No Economies of Scale

Firms in a perfectly competitive market do not enjoy economies of scale. If there were economies of scale in these markets, then the result would be that only a few large firms would remain in the industry.

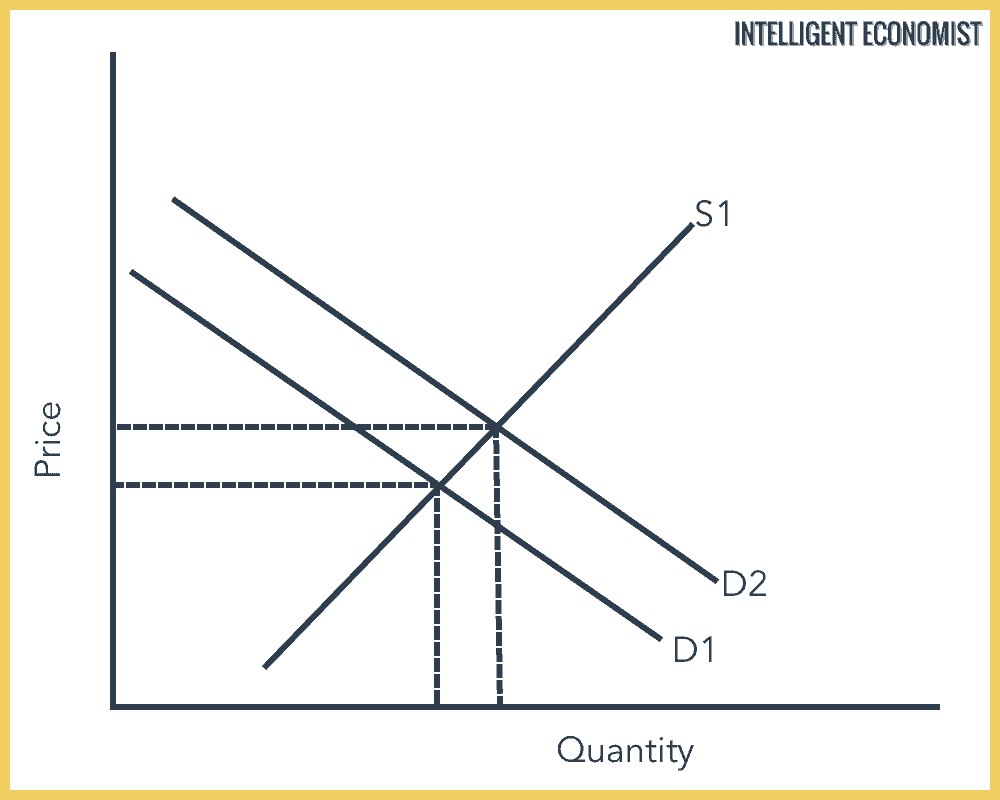

Perfect Competition Rise in Demand

Perfect Competition Rise in Industry Demand

A rise in demand for a good would shift the industry demand curve from D1 to D2. Quantity produced increases to Q2, which results in an upward shift for the Average Revenue and Marginal Revenue curves for individual firms, from D1=AR1=MR1 to D2=AR2=MR2. This shift increases profits since the average revenue curve lies above the average cost curve. The profits are represented by the box between P1 and P2 and 0 to Q2. The firms are now making supernormal profits. This profitability will encourage outside firms to enter the market.

Perfect Competition Rise in Demand Individual Firm

Perfect Competition Industry (Leads To Rise in Supply)

Since there are no barriers to entry, more and more firms will enter the market, which will increase supply from S1 to S2. This will continue until every firm competing in the industry is making zero economic profits. Then no other firms will have the incentive to enter the industry and everyone is back to making zero economic profits in the long run. This makes firms more competitive and decreases inefficiency in the market

Why the price of a product under perfect competition will be equal to the lowest point on the long run average cost?

When price is equal to average cost, it means that a firm would earn normal profits. Note that normal profits are part of average cost.

Thanks you very much! It’s pretty great it’s helpful for both beginner and advance student